Coming out of a record-setting warm winter season, those involved with gardens and lawns should consider how our soils and soil fertility have been impacted by this past winter’s unusual temperatures and moisture patterns. So, what soil processes and conditions have been affected by this past winter?

Moisture levels

To understand how our current weather patterns can impact our garden soil, we need to look at the role that soil moisture might play. After gardens and lawns end their season (either harvest or dormancy), recharging soil moisture becomes a significant issue as the plants have used soil moisture throughout the growing season. When plant growth ends or subsides, the goal is to have precipitation go into the soil and fill soil pores.

Fall rains can be very effective for recharging soil moisture. But when the soil freezes, most additional rain or snow does not enter the soil. This moisture will probably run off during the late winter or spring thaw.

In areas that received sufficient rainfall, the amount of precipitation entering the soil has been much greater due to the record-setting winter warmth and minimal frost conditions. In drier regions of the state, this only pertains to the potential for soil moisture recharge.

Fertility: microbes and nutrients

How can such a mild winter affect soil fertility? While temperature influences soil's physical and chemical properties, its effect is relatively insignificant. However, biological properties and processes are greatly affected by temperature.

Consider all the microbes that live in our soils and the work they do decomposing organic materials (plant residue, compost, manures, leaves, etc.) that are added to the soil. As a rule of thumb, for every 18°F increase in temperature microbial activity doubles. As there is essentially no activity in frozen soil, this winter has benefitted the microbes in our soils, composting piles and containers.

The microbes were more active in the soil and decomposed more in the past few months than normal. This results in more nutrients being available for plants to take up in the next growing season.

Keep in mind that the nutrients of most significance in organic material decomposition from a soil fertility perspective are nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and sulfur (S). So all the nutrients from the existing soil organic matter and added organic amendments will have some extra, positive effect this growing season — assuming they are not lost.

The delicate balance of N

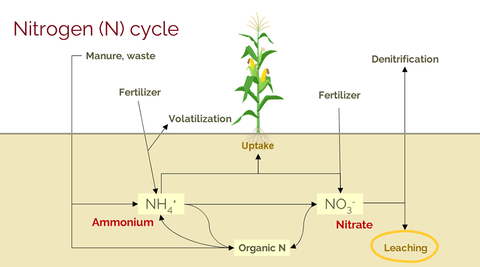

The primary concern with nutrient loss is nitrogen, especially when organic amendments or fertilizer are added in the fall. More specifically, as organic N transforms into plant-available N, the form is ammonium N, which is fairly stable in the soil.

But when soil temperatures rise above 50°F, microbes in the soil can easily convert this ammonium N to nitrate N, a form of N that is mobile in the soil and can be lost through leaching with abundant spring rainfall or via denitrification later this season if the soil gets saturated for an extended period. Thus, a warm winter will likely result in somewhat higher quantities of nitrate N in our soils this spring.

This situation can lead to greater pollution potential from soils to our waters. High quantities of nitrate N in the soil always have the potential to be lost depending on the soil and climatic conditions. The presence of elevated nitrates in the spring has a greater potential environmental impact as plant uptake is minimal, and spring usually has significant rainfall that can cause leaching from soils.

Turf vs. gardens: different N scenarios

Nitrogen management is more of a concern with turf than with a garden this spring. It is commonly recommended to add fertilizer N in the fall with turf, and with the warmer soils this past season, there was more time for the N to convert to nitrate N by the spring-rain season. The fertilizer is inorganic N and the conversion to nitrate N is more rapid with warmer soils. So significant nitrate will probably be present in the spring — and there is potential to lose this nitrate N.

Fortunately, lawns start growing more rapidly and will uptake the nitrate N much earlier this spring. For gardens, adding compost, manures and other organic matter in the fall is not as concerning as fertilizer because these organic N sources must be decomposed first.

While the overall load of nitrate leaching to water systems is relatively low in both scenarios, everyone should manage N to lessen any potential loss of N.

While this year’s weather may be increasing nitrate N in the soil, the most prudent management practice we can do regularly is to not overapply N on our lawns or in our gardens.

Follow the recommended guidelines.

Spring ahead with caution

With record-high temps at the time of this writing, it is tempting to be out planting early this spring. Soil temperatures far above normal might suggest that seeds can be planted with acceptable germination. However, planting seeds and transplants this season should focus on average last-frost dates rather than soil temperatures.

Early planting could result in some early growth, but many of our favorite garden plants are temperature-sensitive and can be cut short by frosts later this spring. And we have yet to see what the rest of April will bring.

Happy gardening!